By: Aaron Zimmerman

A chord is multiple notes played together. We name chords based on patterns that the component intervals form. These patterns, common chords, are the building blocks of harmony. Mastering chords lets you play almost anything by ear, and will greatly enhance your ability to appreciate music.

I’ll break down the most common chords, using three sections, Triads, Seventh, and Contextual Chords. Fair warning, the contextual chords get a bit theory heavy.

Triads

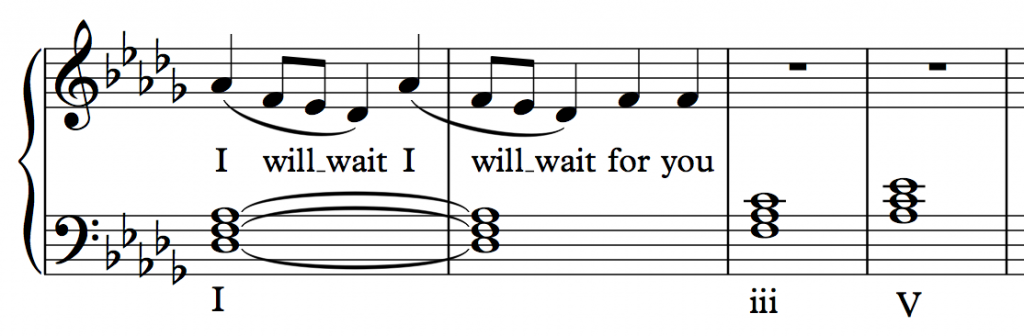

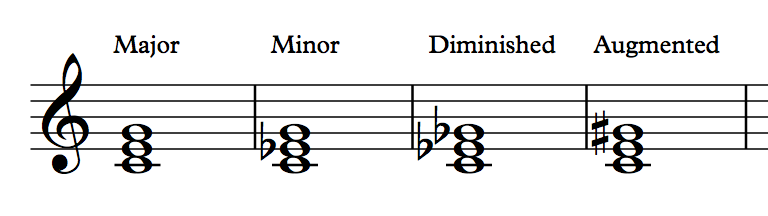

The common triads are the workhorses of harmony. Pretty much any song can be harmonized with these four, especially major and minor. You’d miss the color and subtlety of other chords, but you can play most any song with major and minor. Triads are made of two thirds, one on top of the other. Thirds are also classified as Major and Minor, so to avoid confusion, when referring to an interval, I’ll use a single letter, M for major, m for minor. When referring to a chord, I’ll write out Major or Minor. These four triads are the possible combinations of the two types of thirds.

| Triad | first third | second third | outer interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | M | m | fifth |

| Minor | m | M | fifth |

| Diminished | m | m | tritone |

| Augmented | M | M | minor sixth |

Common Triads

Major and Minor are considered stable, consonant, whereas diminished and augmented are not. Alert systems such as train whistles, police sirens, are often based on these latter two chords, as they are dissonant and attention grabbing. Major and Minor chords are used as the basis for most of functional harmony. See this post for more.

Seventh

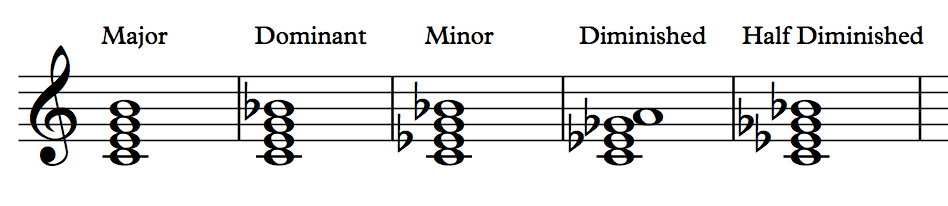

Seventh chords are those that include a fourth note (when compared with triads), a seventh above the root of the chord. Like the above triads, they are based on stacked up major and minor thirds.

| Chord | first third | second third | third third |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | M | m | M |

| Dominant | M | m | m |

| Minor | m | M | m |

| Diminished | m | m | m |

| Half Diminished | m | m | M |

The Major seventh chord is used as a tonic chord, a more colorful version of a I chord. It is often used in pop and jazz. The first chord heard in John Lennon’s Imagine is a I chord, the fourth beat of the first measure, this chord extends to include a major 7th.

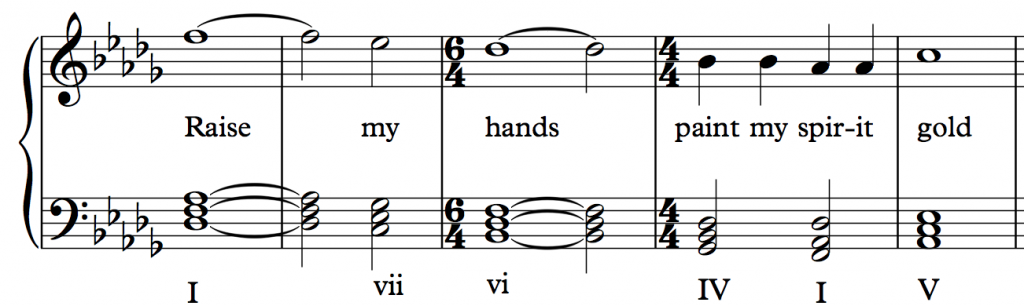

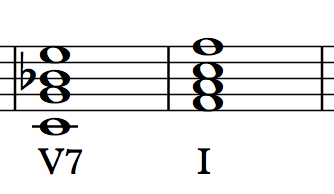

Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC)

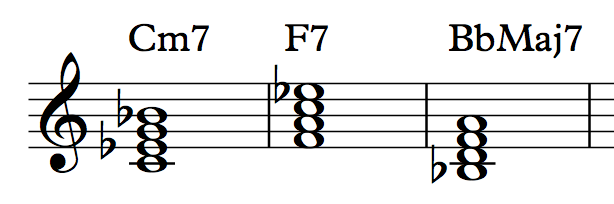

The Dominant seventh chord is used in place of a plain V chord in much of western music. The second and fourth notes of this chord resolve to the first and third of the I chord, in what is knows as a Perfect Authentic Cadence. So, the C Dominant seventh is the V of F major, and the E resolves to an F, the Bb down to an A. This harmonic movement is perhaps the most common in all of music. It is used at the end of many pieces as a way to resolve any harmonic drama, landing the piece in a clear final key.

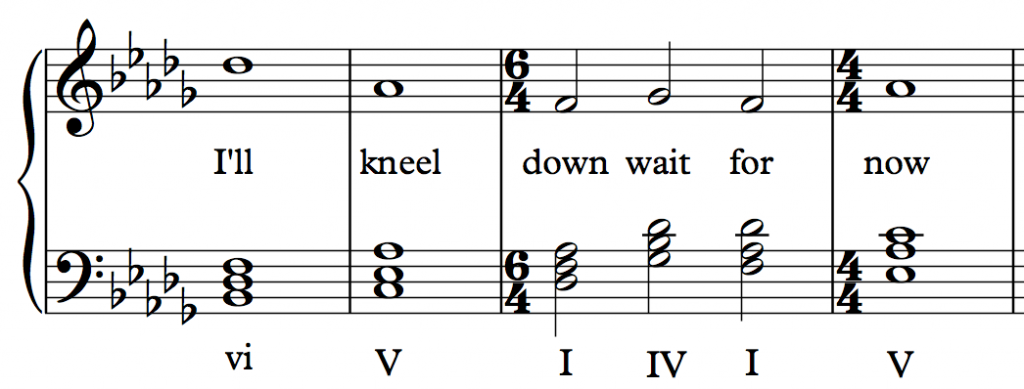

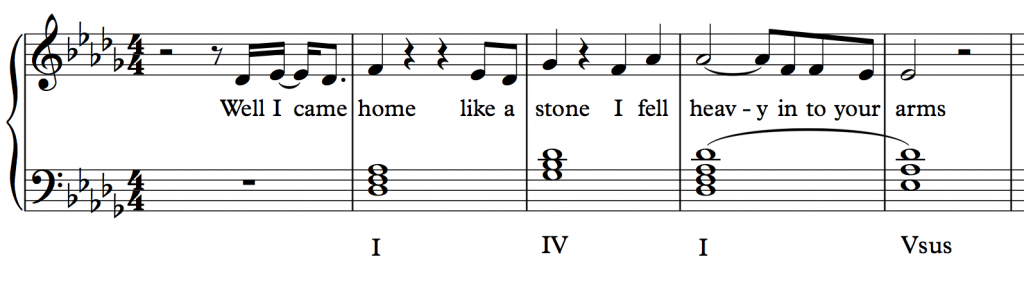

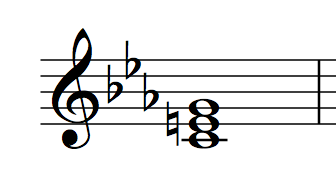

Jazz is built around the chord progression ii-V-I. The V chord is the dominant used above, and the ii is a minor seventh. C minor seventh is the ii chord in the key of Bb major. The progression to the right demonstrates the full ii-V-I in the key of Bb major. The Diminished Seventh chord is a symmetric chord – if you add another minor third on top you are back where you started. This makes it harmonically ambiguous, the C diminished 7 is the same note for note as the Eb, Gb and A. It is a close relative of the octatonic scale in that regard. In fact, the octatonic scale is often called the “diminished” scale for that reason. The lower half of a Half-Diminished Seventh is the same as the fully diminished, but the top note is a half step higher, fitting nicely into many jazz progressions.

Contextual

The above chords were objective, interval based definitions. These chords are different, they are more context based. That is, note for note, they could be classified as something else. Used in a specific context, they have other names, and more importantly, other functions. So rather than base the chords off of a C root as above, these examples are chords, as they would be used in the key of C Major.

Neapolitan Sixth

Neapolitan Sixth

This is another name for an inverted flat second chord. In the key of C Major, that means a Db major chord, inverted once, (making F the lowest note). It resolves to a V chord (G, in the key of C Major). It is used in the song “Do you want to know a secret” by the beatles. The second time the word “really” is heart at the beginning, it is on top of a neapolitan chord that resolves to the V.

Augmented Sixth

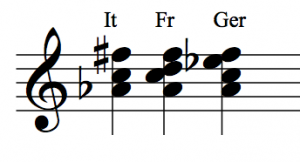

Augmented Sixth Chords

An augmented sixth chord has the interval by the same name as its outer interval, with a third above the root as well. In this plain form, it is called an “Italian” augmented sixth. If we add the second degree of the scale (D in C major), it becomes a “French”, and if we add the flat third (Eb), it is called a “German”. The Italian is enharmonically equivalent (it has the same pitches) as a dominant seventh chord. The difference is that it resolves to the V of the tonic. The chord above would resolve to a G chord, the V of C major. Used as a dominant chord (Ab7), it would resolve to a Db major chord.

Picardy

Picardy Third

A picardy third is when a Major third is used to end a piece that has been in minor key. It was used a lot in the renaissance, as a major third is a more mathematically pure interval than a minor third. So this makes the major third more consonant, and more appropriate for the end of a piece. More about math and acoustics in a future post!

Secondary Dominant

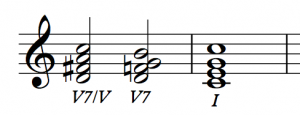

Secondary Dominant – V of V

A secondary dominant is a dominant seventh that is borrowed from another key. The most common usage would be borrowing from the V key – so the secondary dominant is the V of the V. In the key of C major this means a D Dominant Seventh, resolving to a G (the V), which in turns resolves back to the I.