By: Aaron Zimmerman

You turn on the TV. You see 20 or so people dressed in bright colors and helmets. They are just standing around, and then suddenly they run full force into each other. One person runs as fast as they can and another person throws him an oblong ball. The receiver catches it and runs a little ways before flinging the ball at the ground and starting to dance.

You turn on the TV. You see 20 or so people dressed in bright colors and helmets. They are just standing around, and then suddenly they run full force into each other. One person runs as fast as they can and another person throws him an oblong ball. The receiver catches it and runs a little ways before flinging the ball at the ground and starting to dance.

To the average American adult, this is not such an odd sight, but imagine if you had never seen a football game. How much more do you appreciate the game after learning the rules, understanding the objectives, and appreciating the strategy?

This is what it is like to learn harmony. Harmony is the language of music, learning even a little will change the way you listen to music forever.

The three building blocks of harmony are intervals, scales, and chords.

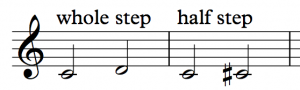

Intervals

An interval is a name for the distance between two notes. Starting from a C, a ‘minor second’ or ‘half step’ takes you to the note directly to the left (B) or right (C#) A whole step would be two half steps, so a D or a Bb.

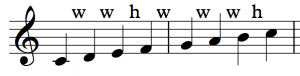

Scales

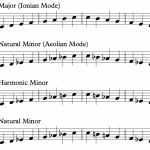

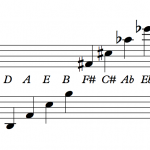

A scale is a pattern of whole steps and half steps. The most common scale, “major”, is the pattern, w,w,h,w,w,w,h. This pattern can be started on any note to create the “major” scale for that note. The vast majority of melodic material in music comes from a single scale. A composer selecting a scale is like an artist picking out the colors of paint they will use for their next work.

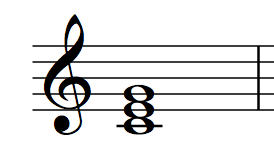

Chords

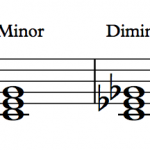

A chord is three notes played simultaneously. Chords are named for their lowest note (called the “root”), and the scale from which the other notes come from. A “C Major” chord starts on the note C and uses thirds from the major scale. (A third is the interval that you get by skipping one note of the scale.)

Harmony

Now comes the clever bit.

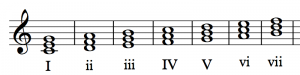

We can take the C Major scale and build a chord for each note, sticking with the same collection of notes (the C Major scale itself), for each root note. This results in the following 7 chords:

By convention, we label these chords with Roman Numerals (numbers are used for so many things in music, this helps distinguish those that designate harmony). We also give them impressing sounding names so we can sound smart at dinner parties. The I chord is called Tonic, the IV chord the Subdominant, and the V chord Dominant.

Harmony is a pattern of chords, a “chord progression”. Usually, chord progressions are designed to create a feeling of departure and return. Think of it like running the bases, we move away from home plate, touching on other chords, before returning home to the I chord, the Tonic.

Sample Chord Progressions:

Pop Music is full of the chord progression I, V, vi, IV.

Pachelbels “Canon in D” uses a longer chord progression: I, V, vi, iii, IV, I, IV, V.

“Hang On Sloopy” and “Wild Thing” both follow I, IV, V, IV…. for the whole song.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony “Ode To Joy” melody alternates mostly between I and V (with a few harmonic flourishes here and there). For the last twenty seconds of the piece, Beethoven repeats and repeats the I chord. This gives the piece a strong sense of finality, of completeness. It is how you can tell that the piece is over.

(Jump to 4:52 to see what I mean about the ending.)

And that’s most of it. Bam! You are now a functional harmony expert. Well, not quite, there are many more exciting twists and turns, but this is a great start. Harmony is the language of music, learning to recognize it is like learning to read. An entire world of appreciation and discovery awaits.

Pingback: Music Theory Rocks | The Wolfric Academy Blog

Pingback: Common Chords |