By: Aaron Zimmerman

“Blues” usually refers to one of two things, a scale or a chord progression.

The bones

The chord progression is 12 measures long, hence the name “12 bar blues”. Here is the progression, with a roman numeral marking the beginning of each bar and a dash indicating the continuance of that chord.

| I | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | I | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | - | - | - | IV | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | I | - | - | - |

| V | - | - | - | IV | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | I | - | - | - |

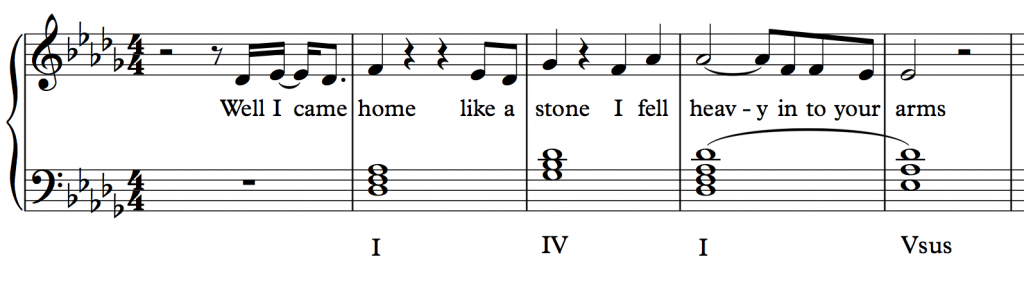

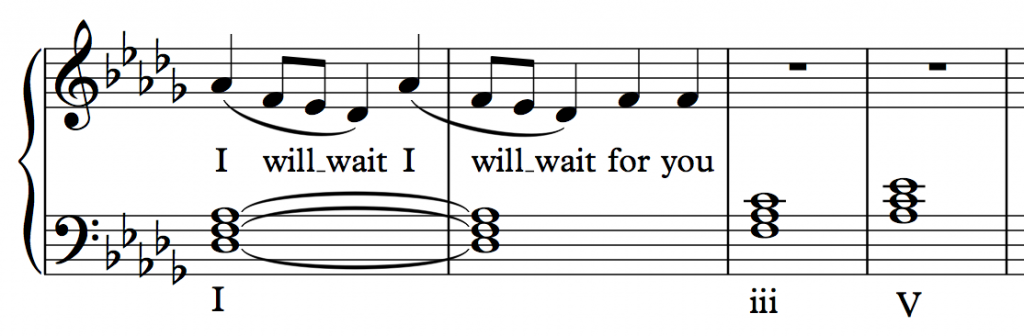

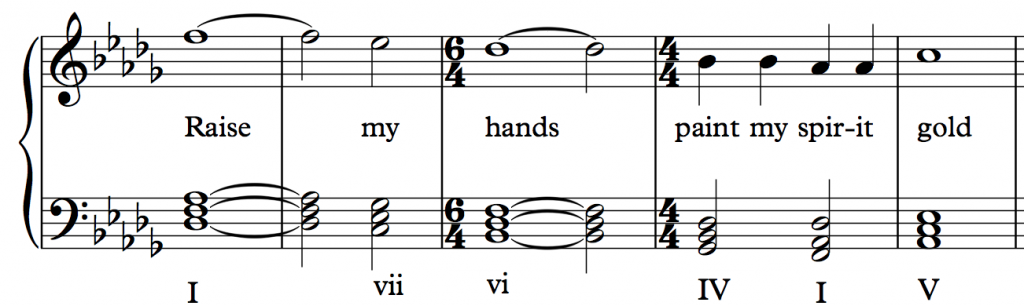

You can here this progression in work in the above song. It starts when the lyrics come in at 0:55.

| 0:55 (I) | - | - | - | 0:58 | - | - | - | 1:00 | - | - | - | 1:03 | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:05 (IV) | - | - | - | 1:08 | - | - | - | 1:10 (I) | - | - | - | 1:13 | - | - | - |

| 1:15 (V) | - | - | - | 1:18 (IV) | - | - | - | 1:20 (I) | - | - | - | 1:23 | - | - | - |

The meat on the bones

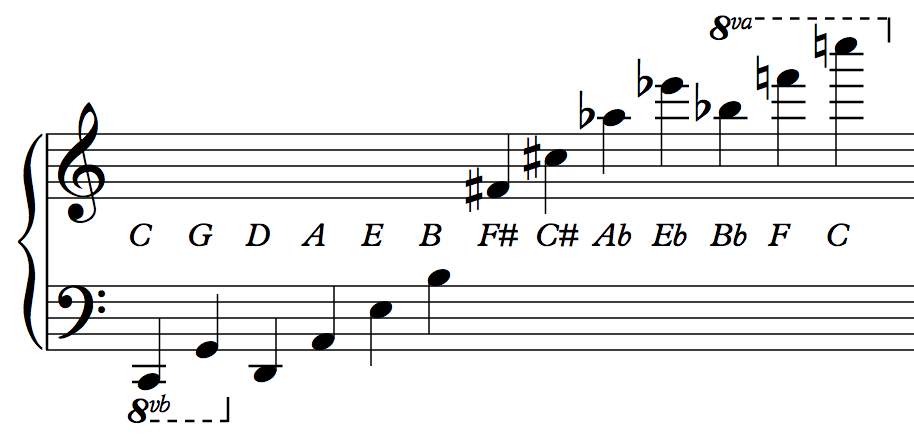

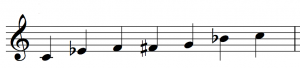

The blues scale is the following notes (in the key of C major).

The Blues Scale

This scale goes hand in hand with the blues progression. You can play each note of the scale with each chord of the progression. That is, if you are improvising using nothing but blues scale notes, you don’t have to think as much about the changing harmonies, and instead can focus on the melody you are playing. In the John Mayer song above, when he plays the fill in riffs and the guitar solo starting at 1:54, he is using the blues scale. Notice how the notes he is playing doesn’t change with the harmony.

The skin that holds it together

The most important thing in blues, and any improvisation, is time. The idea of a steady pulse is critical to holding the ensemble together. They don’t have music, all they have is a chord progression, and they jam on top of it, using a steady beat as the mechanism of staying together. You can hear the strong pulse in John Mayer’s recording above. The beat is heavily accented with bass, drums, and guitar.

The clothes and cool hats

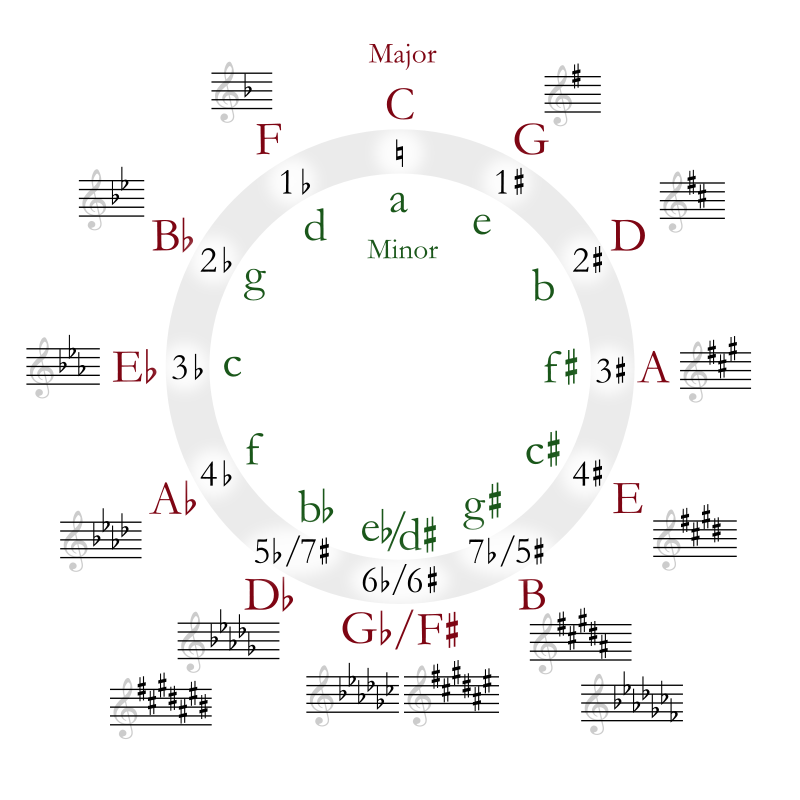

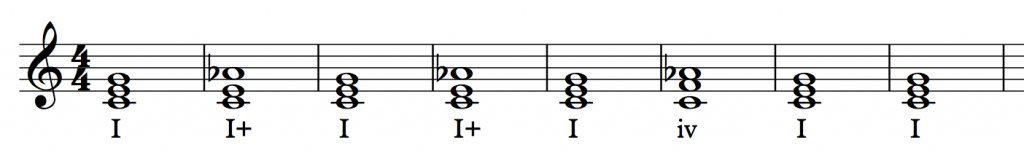

The blues progression is like a vanilla cupcake hot out of the oven. It is good, fantastic even, but when enhanced with some frosting, filling, or whatever goodies you prefer, it is still better. The tune above uses a slight variation, using the bII chord on the fourth beat of each “I” measure.

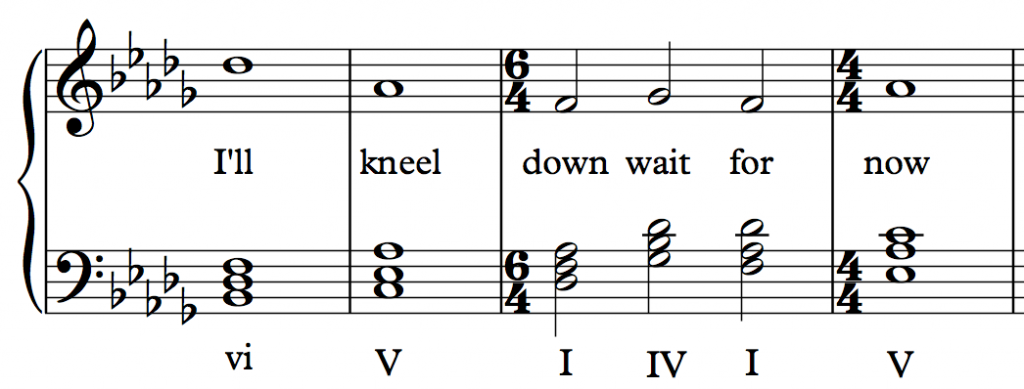

Jazz players like to make things more complicated, so he progression ii -> V -> I is often sprinkled over the basic blues progression, turning it into the “jazz blues”

| I | - | - | - | IV | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | V | - | I7 | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | - | - | - | IV | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | VI | - | III | - |

| V | - | - | - | IV | - | - | - | I | - | vi | - | ii | - | V | - |

In addition to the ii -> V -> I at the end (wrapping around to the top), the end of lines 1 and 2 also use this progression. But their target key – the I they are moving toward is the IV and the V chord, respectively. Here’s a classic example of the jazz blues.