By: Aaron Zimmerman

Ask an adult who studied piano about scales, and they will likely roll their eyes and scowl. Scales bring boring repetition to mind. We tend to think of them the way football players think of push ups. “That’s three wrong notes in a row, drop and gimme F# Major!”

But this is unfortunate. Scales are our friends, they make music easier to understand and learn. Scales are one of the building blocks of music.

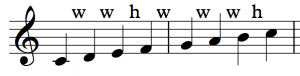

A scale is a collection of notes, usually formed by a pattern of intervals. The scale is named by the note it starts on, and the pattern the intervals follow from there. The “Major” pattern goes:

Whole, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Whole, Half.

If you start this pattern on a C, you would play all of the white notes, yielding the C major scale. Stay tuned for a follow up post that will go into detail on other scale patterns.

From a practical standpoint, music is full of actual scales. Once you can play scales, you can play most Beethoven and Mozart. Ok, there is a bit more to it, but not much really. Page after page will just be variations on playing a scale up and down.

Learning to play scales

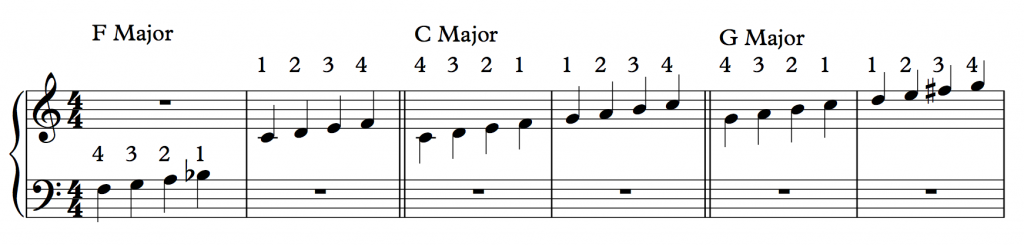

Phase 1 – “Four finger” scales. A few months into lessons, after basic concepts like rhythm, counting, etc, are mastered, students can begin playing one octave scales, with the notes split between the hands. So, using C Major as an example, the left hand plays “C, D, E, F” (starting with the 4th finger), and then the right hand plays “G, A, B, C” (starting with the thumb).

Phase 1 – “Four finger” scales. A few months into lessons, after basic concepts like rhythm, counting, etc, are mastered, students can begin playing one octave scales, with the notes split between the hands. So, using C Major as an example, the left hand plays “C, D, E, F” (starting with the 4th finger), and then the right hand plays “G, A, B, C” (starting with the thumb).

Phase 2 – Start thinking about scales as patterns, not just notes. This is emphasized by the observation that you can move the root of a scale up a fifth, and play the same notes you just played, with the middle finger of your right hand playing a half note higher than previous. That is, take the notes from C major, play them starting on a G, only raising the third finger of your right hand a half step. And this can be repeated through the whole circle of fifths. The inverse is also possible, move the root down a fifth, and now lower the thumb of your left hand a half step.

Phase 3 – Start playing scales 2 octaves, hands together at a moderately slow tempo. Usually this is somewhere in the late beginner, early intermediate stage, whenever it is technically possible to cross fingers. From there move quickly through the scales, not worrying about perfecting the fingering or perfectly smooth playing, but rather emphasizing the scale as a pattern in and of itself. The starting note doesn’t really matter.

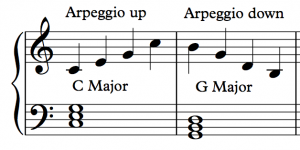

Phase 4 – Play scales 4 octaves at a time, at a moderately fast tempo. Emphasize smoothness in crossing over fingers, play all notes with a consistent, solid tone. Introduce variations like playing in triplets, playing staccato to keep it interesting. Part 2 will give some more examples on variations to try.

Scale Finger Patterns

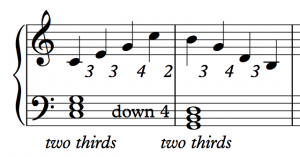

No piano fingering is one size fits all, but there are well established scale fingerings that will probably work the best. With 2.5 simple rules, remembering when to use which finger is easy:

1) Never play a black key with your thumb

2) Play in groups of 3 and 4

2.5) Try to minimize the number of cross overs

Try it, it really is that easy. Scales that include a lot of black keys are the easiest because of rule 1. If you only have 2 white keys, you know right off which keys your thumb will play. Note that this is only true for 7 note scales.

Wrap up

Scales lend themselves to warm up sessions. They are not technically challenging (at least not after a few years of practice), and they are a good pivot point for your brain and your fingers to shift into music mode.

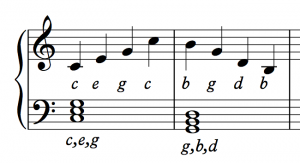

But don’t think of scales as just for warming up. There is a theoretical side to them that makes them an integral part of any music education.

Keep an eye our for part 2, wherin I will give details on different types of common scales, and suggest some ways you can vary scale practice to keep it challenging and engaging.